AI Data Centers, Defense Production and The Next Hot War

Understanding How Defense Policy is Driving the AI Bubble

The last week has brought about both laughter and bemusement at the suggestion of OpenAI’s CFO (and subsequently Sam Altman) that the US Federal Government could, would and potentially should backstop the production, construction and purchasing of AI data centers and the materials therein - including high-end GPUs - in order to provide confidence for the “growing AI industry” to capitalize as much capacity as possible to “meet the needs of the broader economy” (these are not direct quotes but euphemistic interpretations.

While this is perceived as entirely self-interested (however likely that is) it also represents what is not necessarily a bad bet for the US taxpayer (or bondholders). Why is this the case? It has precedent in both the distant and recent past, it functions as dual-use technology that can be a critical US defense-industrial differentiator, and it promises the possibility of totally bankrupting the AI Model companies, which should be appealing to anyone who hates them. As such, as far as the US political process goes - it’s a 360-win. Here’s the real story behind it.

US Defense Production - CHIPs Act and Otherwise

The Defense Production Act of 1950 was passed in order to maintain the abilities granted to the US executive brand in the War Powers Acts of 1941 and 42, which enabled the Roosevelt Administration to mobilize private businesses for war production by means that ultimately led the US engagement in both Europe and the Pacific, support of its allies and the defeat of the Axis Powers.

Since World War II, Defense Production powers have been used to maintain advantages in heavy industry, specialized alloy production and the production of new materials to maintain a technological advantage over both the Soviets and other adversaries. In more recent years, it has been used increasingly for domestic requirements which pose a strategic risk, including COVID-19, while the Biden administration also invoked it for “critical minerals for battery storage and electric vehicles” as well as baby formula.

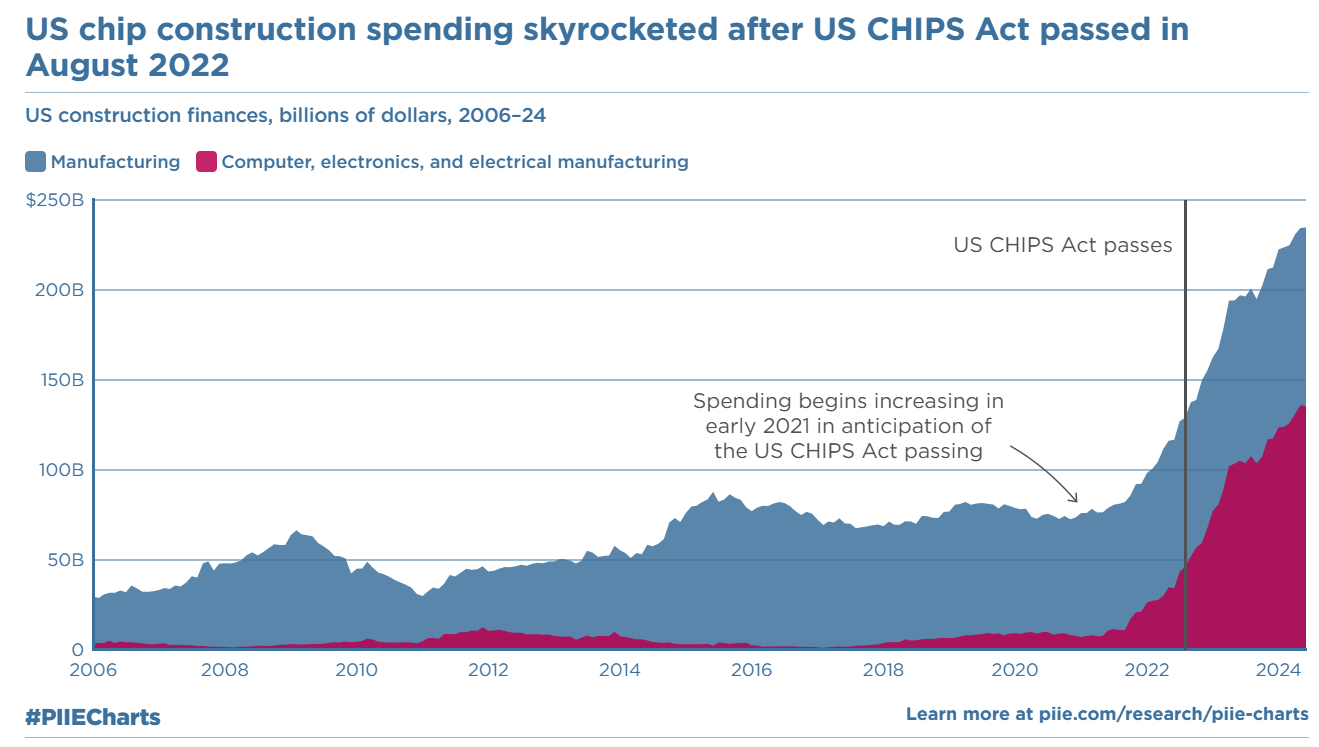

While many recent usages are, though somewhat trivial from a legal perspective, clearly overreaches in regards to the original spirit of the law, separate legislation passed during the Biden Administration with bi-partisan support make it clear what the Defense-Industrial Complex (as an apparent “entity”) intend to achieve in collaborating with the AI industry. The CHIPs Act effectively provided hundreds of billions of dollars in direct and indirect incentives to re-shore manufacturing of advanced chips in order to maintain the defensibility of both US defense and non-defense computing needs. Even more of a strategic surprise, this was already an issue which was addressed with legislation that encouraged domestic production at the end of the Reagan Administration, though with mixed results.

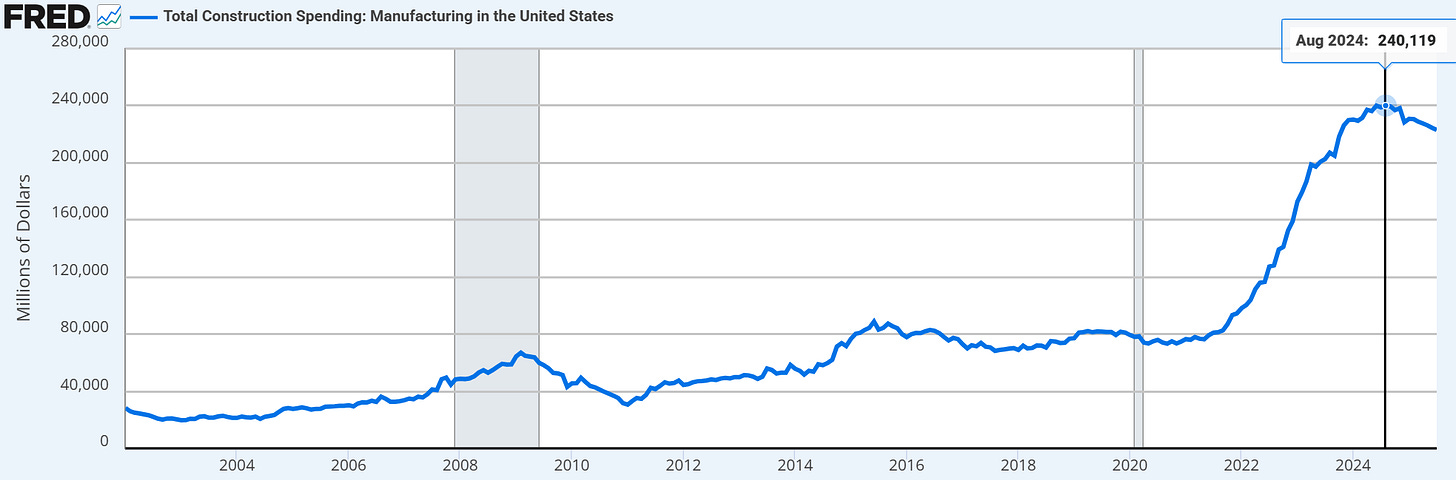

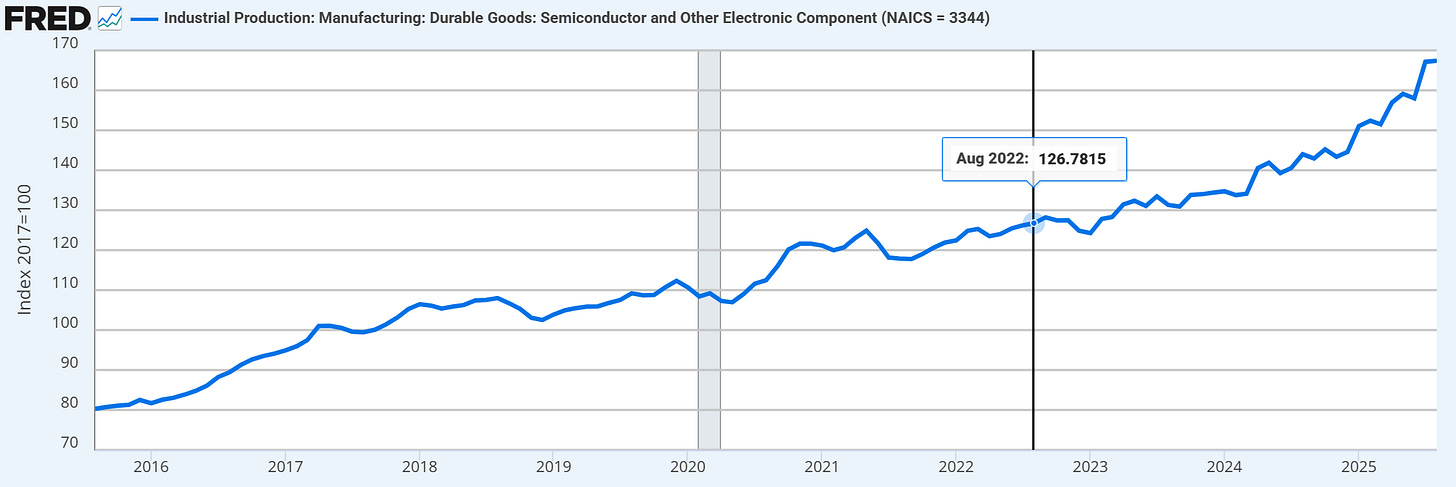

In anticipation of the CHIPs Act passing, manufacturing construction spending already began to surge in 2021, peaking in August of 2024, while actual semiconductor production began a contemporaneous increase. It could be considered good luck or mysterious planning that this “capacity-building” also contributes to the overall capacity to build AI data centers, which drove more than a full percentage of US GDP growth in the first half of 2025.

source: https://www.piie.com/research/piie-charts/2024/us-chip-construction-spending-skyrocketed-after-us-chips-act-passed

source: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/TLMFGCONS

source: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/IPG3344S

AI Capacity as a Defense Differentiator

AI is an obvious dual-use technology in the same way that diesel engines or effective steel manufacturing can be. Its potential use cases are so ubiquitous that there is hardly a defense application which will also go unaffected. Much as emergent players engage in bubble-pushing, companies like Anduril are developing everything from autonomous drones to AI-enabled headsets for close-quarters combat. It is most likely that similar projects also exist in the prime defense contractors, and the usage of remote-monitoring and these sorts of combat enablement methods is as old as carrier pigeons and hot-air balloons, but also applicable to obtuse measures like the McNamara Line in Vietnam, which used early digital and computer technology to create an invisible barrier on South Vietnam’s borders with the North and Laos.

As we speculate about the value of AI in defense applications, it is important to understand that it will take place in an accelerated manner upon the exercise of actual conflict. Similar to the progression of the Ukraine War, future wars between peer adversaries will likely include segmented, tactical missile swarms as part of active communication, negotiation and peace discussions which amount to little more than economic partitioning and “wrestling for control”. In all wars of previous generations, various levels of command exist to communicate active and passive boundaries - both to provide more methodical fighting rhythm - but also to spread mis- or dis-information and gradually achieve tactical outmaneuver at critical chokepoints, whether this is as old as Hannibal’s march through the alps or as recent as the Wehrmacht massing forces in the Ardennes.

It’s impossible to know what is truly happening in war at any given time, but most tactical advantages are realized by the perception of credible and non-credible threats and the attention span of an adversary to respond to them The Ukrainian incursion into Kursk in August 2024 is a clear, immediate example of this - something which took Russia by such surprise that there was still a Ukrainian presence there as late as June 2025.

The possibility of AI-driven warfare, whether it reads like a Palantir SEC statement or not, is that there will be a step-function increase in visibility across not only battlefield positions but also in the economic and productive capacities of the adversary at all times. In place of the traditional example of, for instance, the Allies bombing a German ball-bearing factory with unclear levels of precision in order to disrupt supply lines, we will likely see targeted hypersonic missile swarms on antimony-processing sites or similarly obtuse (and generally inexpensive, but time-intensive) production and development sites which will, as a knock-on effect, increase lead-times of critical supplies to central battlefield, but not manifest as tactical disadvantages until an endgame becomes apparent to all parties - at which time negotiation may or may not still apply.

This implies that winning in modern warfare, as a strategic necessity of all modern states, requires both strategic capacity and immense patience in order to realize a quick series of tactical advantages which accrue to victory, only at the very end (to gratuitously quote Jeff Foxworthy, it’s dumb to say that a missing item is “always in the last place you look”). This has the same tactical character as Alexander conquering east or the Germans taking Paris, but nation-states now have an advantage in it being clear how sophisticated and imbalanced military supply chains can become if not closely tended to. Why this is also increasingly obvious in the popular consciousness, maintaining AI capacity can be made apparent and critical in that it can be turned to visibility, maneuver and, when the time comes, attack, making it essential to maintaining the security of a modern state, and yes also sometimes its citizens (we know that’s not always necessarily the first priority).

Bankrupting the AI Model Companies to Achieve Decentralization

OpenAI deserves the credit of thoughtful product design in its first launch of ChatGPT and the subsequent explosion of both interest and actual utilization of LLM-powered AI tools. There is no other firm or group of people more responsible for the acceleration of interest and relevance that this technology has experienced.

And yet, as is the case with General Purpose Technologies, it is often very difficult for leading firms to capture and monetize the important idea which is behind its initial development. While Thomas Newcomen invented the steam engine, James Watt implemented the improvements necessary to make it popular. His 18th-century improvements hardly permitted him to collect royalties on all steam engine production that followed, and if you were to consider which firms most benefitted from the steam engine, it would be the railroad builders of the late 19th century - many of the families of whom still influence American politics and culture to this day.

If we suppose that the firms which capture the most value from General Purpose Technologies are those which build the most effective value-chains around them, then OpenAI attempting to leverage data center capacity for consumer-facing applications would be one flavor, while Anthropic generates its models for work and coding, and different model-builders purport to offer more purpose-specific models and data sets that have differentiated value (i.e. a “moat”) for their specific customer base or community. The issue with each and every one of these firms - aside from actions which could be considered effectively malicious or socially toxic (whether it’s Sam Altman’s false promises or Dario Amodei’s fear-mongering) - is that centralization inherently breeds the sort of monopolistic, protectionist mercantilism which is toxic to society as a whole, and indeed led to the trustbusting movement and the overall outcomes of the “Progressive Era” that followed the Gilded Age (chiefly of railroads).

It’s not that the Model-Builders are malevolent actors, its that they are - by consequence of our particular economic system - willing to pursue malevolent actions as a consequence of their commercial interests. This is more of a social risk which becomes apparent as power, or “value-produced”, becomes more concentrated. As such, defense production for data centers is an almost perfect hedge, because it gives the government clear and reasonable license to commandeer AI capacity into other ends when necessary.

As was the case with the trustbusting movement, activism played a part, but ultimately the power of both government and the legal system was required to open up key industries in a way that permitted more equitable wealth distribution and longer-run economic growth. In the modern context, society would benefit from the ability of government to commandeer AI capacity for both defense and “defense-adjacent” applications, even on the basis of simple or popular economic benefit. There are certainly always other risks that come with government control, but they also offer a hedge against the obvious risk of overly centralized private control.

At the same time, the building of AI capacity for LLM usage is not necessarily as worthwhile as the dual-use that same AI capacity offers when it comes to machine vision, various manufacturing and transportation applications, and the ultimate capabilities that may come with humanoid or service robots which could effectively solve both skilled and unskilled labor crises, and underly what could effectively be a future market-driven abundance agenda.

In the end, if model-makers seek government guarantees, they may not just get screwed - everyone else may benefit as a result.