The Destruction of the Capital Cycle

Otherwise known as "10 things I hate about Keynes"

There’s an apocryphal quote - I simply can’t find the source, to the effect of “Anyone who tells you something isn’t about politics is actually saying the opposite”. The effect of this is to say: anyone who tells you something is not about a certain characteristic or trait, is in fact trying to hide the truth of the matter, and in the case of the Federal Funds rate of the US Federal Reserve, there is no more political a tool than that.

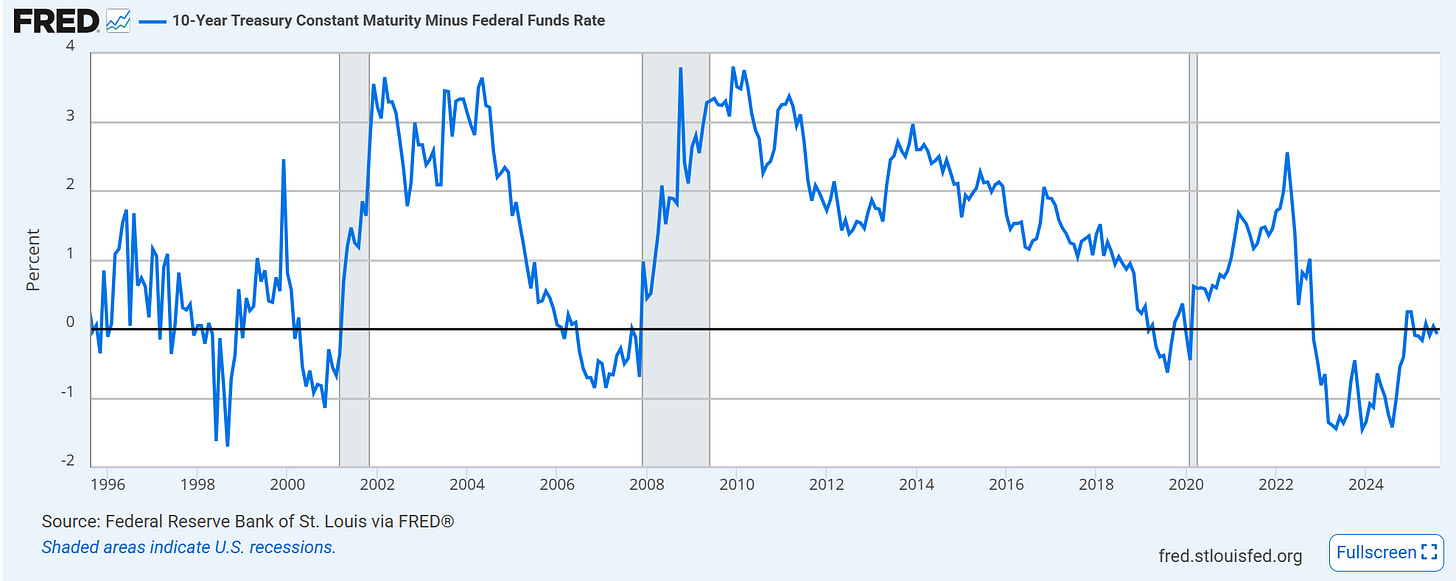

Case in point, the 10-year t-bill minus the fed funds rate, for the last 30 years:

Source: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/T10YFF

The Fed effectively had no problem being political from 2002 to 2006, from 2010 to 2016 and from 2020 to 2022. The only challenge in 2022 was that - after multiple quarters supposing that inflation was “transitory” (inflation that was financed by the Fed), they jacked up rates to bring inflation to a halt.

Now, we are supposed to believe that the market is guiding the federal funds rate when we know there is as much as a 400 bps spread between the fed funds rate and the 10 year t bill in the last 30 years. It is obviously a preposterous supposition, but a lie big enough to be believable, and it originates in a perception of the unpopularity of the Trump regime.

Whether the Trump administration is unpopular or not doesn’t matter, because there are a few factors which compose a healthy business cycle, and the fed mostly works against them. Firstly:

Neutral start: inflation has been cleared away, unemployment is stabilized after some cuts, technology and business investment are predictable with valuations that don’t exceed decent multiples and profitability maintains balance with growth.

Expansion: Growth begins to outweigh profitability, as businesses and investors see the economy heating up and become overly ambitious upon the fear of missing out.

Peak: Growth is now pursued at all costs, even if the net marginal benefit of growth is declining (e.g. every new dollar spent on product development or customer acquisition fails to bring a dollar of return on a reasonable time horizon)

Weakening: Companies and investors lose heart, become too conservative and in effect throw bad money after good - this is to say, they made objectively “good” investments in an expansion phase but now lack the wherewithal to sustain those decisions as signs of contraction emerge

Decline: Market participants give up the ghost - people forget the good times ever happened and retreat to strategic positions for the sake of survival.

Return to Neutrality: Eventually, slashes in investment and employment reach their own point of diminishing returns and the economy returns to a fixed level of activity which is unchanged barring external shocks. In this period, confidence eventually returns and businesses slowly take on more risk to expand and grow.

What we have witnessed in the last few decades is not a respect for the typical highs and lows of the business cycle, but instead a “politicization in neutrality” that leads to front-running Keynesian overreach. This could be perceived as much the same problem of the 1930s, in which public sector overreach crowded out productive private investment, leading to persistent employment and wage issues deep into the 1930s which were only effectively solved by the fixed capital formation that came with World War 2, and when turned to beneficial consumption (instead of bullets and bombs) led to a “Golden Age of Capitalism”.

Ultimately, while Keynesian policy became widespread in this period in order to sustain growth, the actual bases of growth which enabled economic expansion were developed in the late 1930s and 40s. With this capacity developed, new investment simply sought to maximize utilization of pre-existing machine tools and information technology, and as that capacity was maximized, growth began to slow into the 1960s and 70s, where eventually new investments in IT and automation would take their place as growth drivers (of whatever growth there was).

However, by that time, cuts already had to be taken in the welfare states of the West, and while birth rates and labor productivity stagnated, governments had to take on more of the burden of both public and private investment in order to sustain the perception of growth, ultimately leading to the uncontrolled deficits - with no meaningful growth - that we see today.

So what requires a return? Pain, but not pain as we understand it: we are facing a total decapitalization of both the west and east, a total destruction of the business cycle, a total return to bare minimum fixed capacity which is only justified in the run up to a massive war (or justifies the massive war, in order to utilize that).

And what do the statistics say about all this?

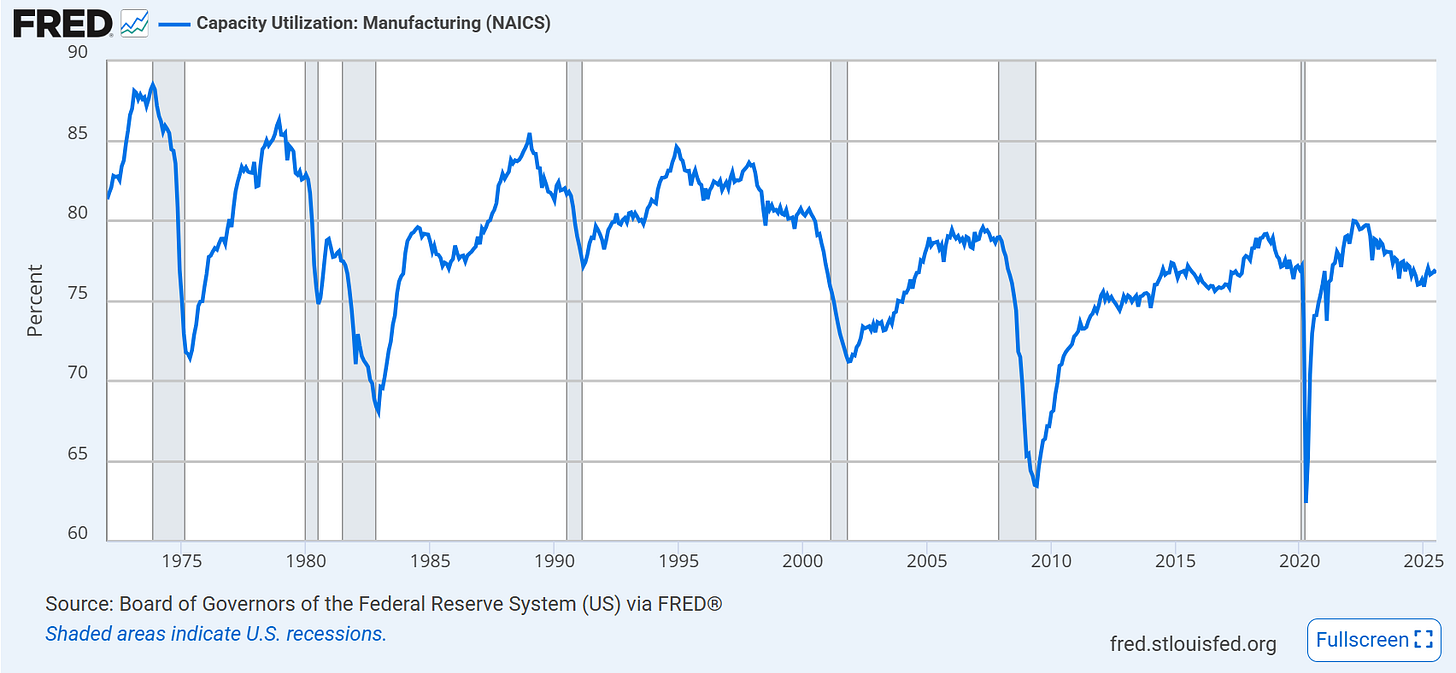

source: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/MCUMFN

Quite a bit in fact, the above indicates that machine utilization has essentially never returned to it’s peak before the 70s bust, and the rates of utilization today are essentially recession-era rates in the 1990s.

Could this be that digital technology, automation and other investments provide such meaningful leaps in capacity for every dollar that new capacity is simply outpacing the ability to consume it? That is quite possibly true, but if all that is the case, that’s also an argument for even lower secular interest rates.

And at the same time, that’s not a conversation the fed is interested in having.