The United States and China: Has The Torch Already Been Passed?

China's Industrial Capacity is a Signpost on the Trail of History

“The Americans cannot build airplanes. They are very good at refrigerators and razorblades.” - Hermann Goering

Online media is awash in stories of Chinese innovation recently - record-spanning bridges for the paltry sum of $300 million, “bone glue” that heals fractures in minutes, age reversal in primates. The reporting of these advents could very well be misinformation, white lies or part of a well-orchestrated propaganda campaign, while traditional criticisms of Chinese “safety”, “accuracy”, “soundness of execution” can also apply, but the rate of development is certainly startling - particularly on the heels of Xi Jinping’s recent military parade and open courting of Putin and Modi in the public eye.

Many events on the international stage are simply part of the day’s soap opera, designed to maintain our attention and get us to worry about things we cannot control - including things even the leaders of nations can neither truly influence or prescribe. The development of a society obviously depends in part on sound leadership, but it also depends on the will and quality of the people who will permit it to achieve great heights without supervision, a collection of many individuals who are willing to take risks, fail, learn and iterate - while also being permitted the resources to do so.

What is much easier to look at and draw accurate conclusions from, and perhaps much more concerning to the pugilistic among us, are the raw numbers. In particular, China’s gross capital formation would now appear to exceed that of the United States, and the rate of growth is only accelerating. One example is that China now maintains 54% of global industrial robotics installations, and a majority of those are sourced from within its domestic robotics industry. While US capital invests record amounts in AI data centers (at the cost of other forms of fixed capital investment), China is surging forward with surplus capacity in every single critical category of manufactured goods, supplying the world while building their own shop. The scale of the numbers is astounding, but it also serves as a historical prelude to transitions we have seen before.

China Surpasses US in Gross Fixed Capital Formation

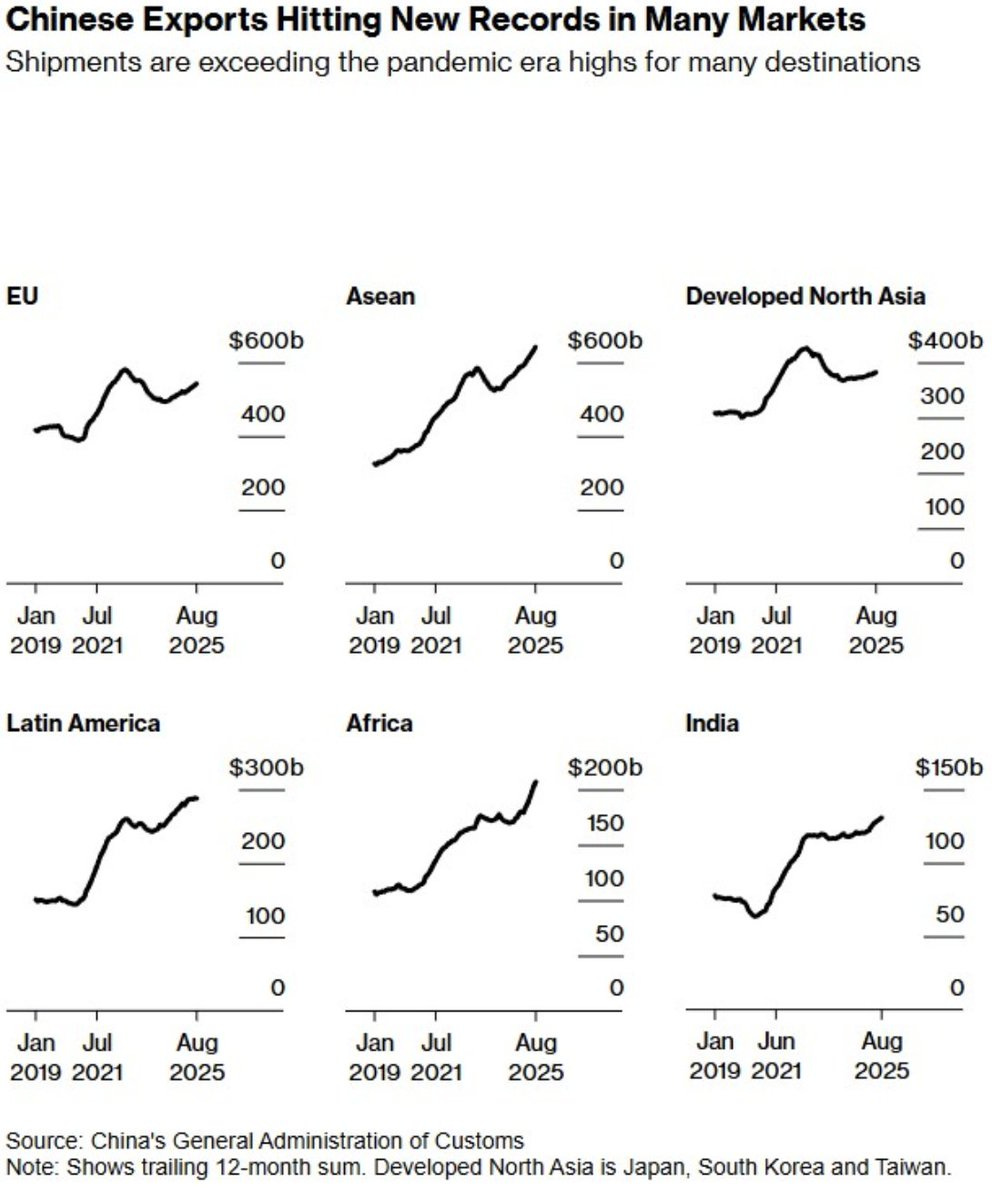

Today, China represents the majority of global industrial production and also global exports. It now offers $3.5 trillion in exports to the world on an annual basis, the same size and the next two closest exporters (the United States and Germany) combines. Interestingly, it also imports $2.5 trillion in goods, trailing the United States globally, but maintaining sizeable trade deficits with Taiwan, South Korea, Australia and Brazil, and substantial imports (though mostly balanced trade) from Japan and southeast Asia.

This is executed while running a significant trade surplus with the United States, essentially re-routing US consumption into capital surpluses through a broader Asia-centered economic system which previously depended on “cheap” Chinese labor, and now depends on substantial Chinese fixed capital. China’s fixed capital formation approaches 40% of GDP while the United States hovers around 22%, along with most other EU countries. Part of this can be attributed to lower GDP per capita (ignoring PPP) which effectively “reduces the denominator”. With the added effects of high savings rates and significant industrial financing through state-owned enterprises, it’s obvious that China is increasing its value-add every year, and hence increasing potential profitability and power within the global financial system.

Against current GDP ($29.18 trillion for the USA and $18.74 trillion for China), China’s fixed capital (as the percent of GDP mentioned above) would be around $7.5 trillion, while that of the United States would be $6.4 trillion. This is a critical signpost because, though we know that China dominates the world in manufacturing production and exports, it is also clear that they have now surpassed the United States in total manufacturing capacity - essentially the ability to produce production. Without some fundamental change in the direction of China, this means that it has taken a lead that it can otherwise not give up unless the United States finds a way to provoke a conflict, and with the general mood of the United States today, what would be the point of this anyway except to mask the social discord which is already eroding the ability of the country to act in a unified matter to begin with?

US Competitiveness is Cope?

While China has constructed a highly optimized system for value-creation, and through regional dominance could impose more strategic certainty that would allow for a consumption-driven economy, bears will say it does not necessarily have the capacity to truly become the “undisputed” center of the global economy. Primary concerns here are: external dependence for resources, machine tools, chips, high-value added optics, avionics and other specialized equipment.

On a per capita basis, individual productivity - even in manufacturing, clearly remains higher in the United States, while long-term birth rates and population dynamics mean that the sort of retrogression we expect in China (which will necessitate even greater leaps in productivity) will not be as problematic in the United States. While manufacturing utilization is effectively comparable in both nations, the reserve capacity of the United States is higher in its advantage in raw materials. Even if China were to “capture” ASEAN countries in a Tojo-like gambit, it would lack the long-term complexity and defensibility that the continental United States maintains, along with the ability to project power into Central America and the broader swath of the Pacific Islands, which China would be unable to sustain from a supply perspective for at least another few decades.

In this timeframe, China’s total population will also have begun to contract significantly, and will only be 50% larger than that of the United States by the year 2100 (at current rates of decline). US retrenchment is effectively the path to “victory” against China as a “Strategic Competitor”, while engagement with Russia and Europe is also unnecessary to sustain broader capacity - the US competes with Europe for its most strategically valuable export, high value-added machine tools, and this means that Europe is not strategically necessary to the United States except as an economic subject, which is effectively proven by the imbalanced resolution of the US-EU trade framework.

While the US today is suffering an economic transition that in part comes down to the traditional wages of empire, which are inflation, stagnation and debt, a United States that is forced to fix its financial position will ultimately be in a better position to make use of its natural resources and its still relatively patriotic population. China paved over nearly 21 million hectares of farmland between 1979 and 2008, and efforts to reclaim farmland have been plagued with the inefficiency of government largesse. China may assert imperial ambitions in the ASEAN region as a matter of “self-respect”, but it will ultimately suffer the same wages of empire that have brought the United States to a relative “low”.

The above case is savvy, and yet, it does not fully respect history. China is not without its acolytes in Taiwan, and Taiwan represents China’s largest trade deficit. Taiwan’s ability to produce advanced chips and electronics, and Europe’s ability to produce the lithography machines that help manufacture them, mean that the value chain in the Digital/AI “economy” in which the US is making massive investment… is deeply invested in China. The US is chasing the gold rush, the world-system is selling them the picks and shovels, while essentially building no meaningful new capacity in other forms of manufacturing, automation, durable goods production, or making a meaningful effort to substitute the vast swath of imported goods it relies on (except “discouragement” through tariffs).

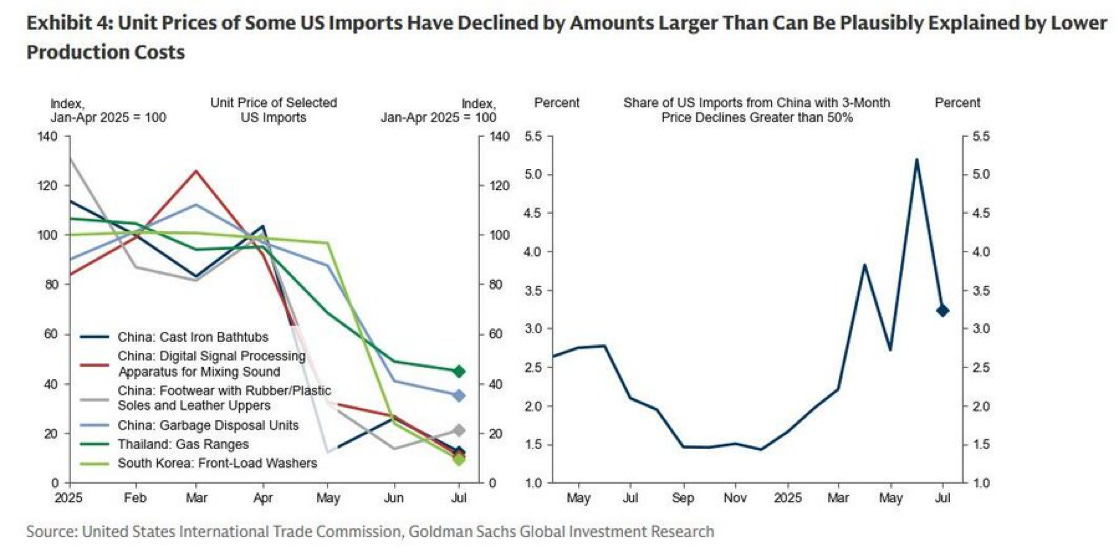

Every nation outside the United States has pursued an aggressive industrial policy, and it shows, while the United States not only lacks the political will and financial flexibility to begin to make aggressive new investments in fixed industrial capacity - it does not even have the capacity to begin to build that capacity, while China is essentially able to overproduce to such an extent that they have absorbed US tariffs without a fundamental change in their global trade relationships.

China’s industrial capacity - whether in labor or machine capital - is so substantial that it is able to effectively win any “price war” that tariffs impose except in the most absolute circumstances (e.g. 10,000%). Moderation of these asymmetry can only come from the US applying 2-3 decades plus of industrial investment (effectively what it has exported since the end of the Cold War) in addition to retaking the vanguard of manufacturing technology - all while it has hollowed out its internal talent pool through the predominance of foreign students, and seen the vast majority of its “tribal knowledge” in machine technology and hands-on innovation disappear with the retirement of successive generations of manufacturing workers, having trained nobody to replace them, because policy of the 80s and 90s dictated that it wasn’t necessary to do so.

How Industrial Transition Drives Financial Transition

There are a variety of financial factors which imply that the US simply cannot sustain its global position at the center of the post-war financial order. In order to understand why that is the case, it’s important to understand how the United States came to its preeminent position.

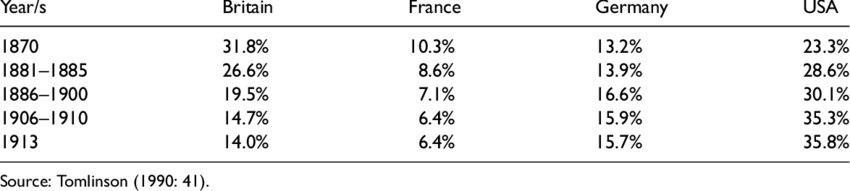

Below is the global share of Industrial output for five major countries prior to World War I:

source: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/360789559_The_distinctiveness_of_state_capitalism_in_Britain_Market-making_industrial_policy_and_economic_space

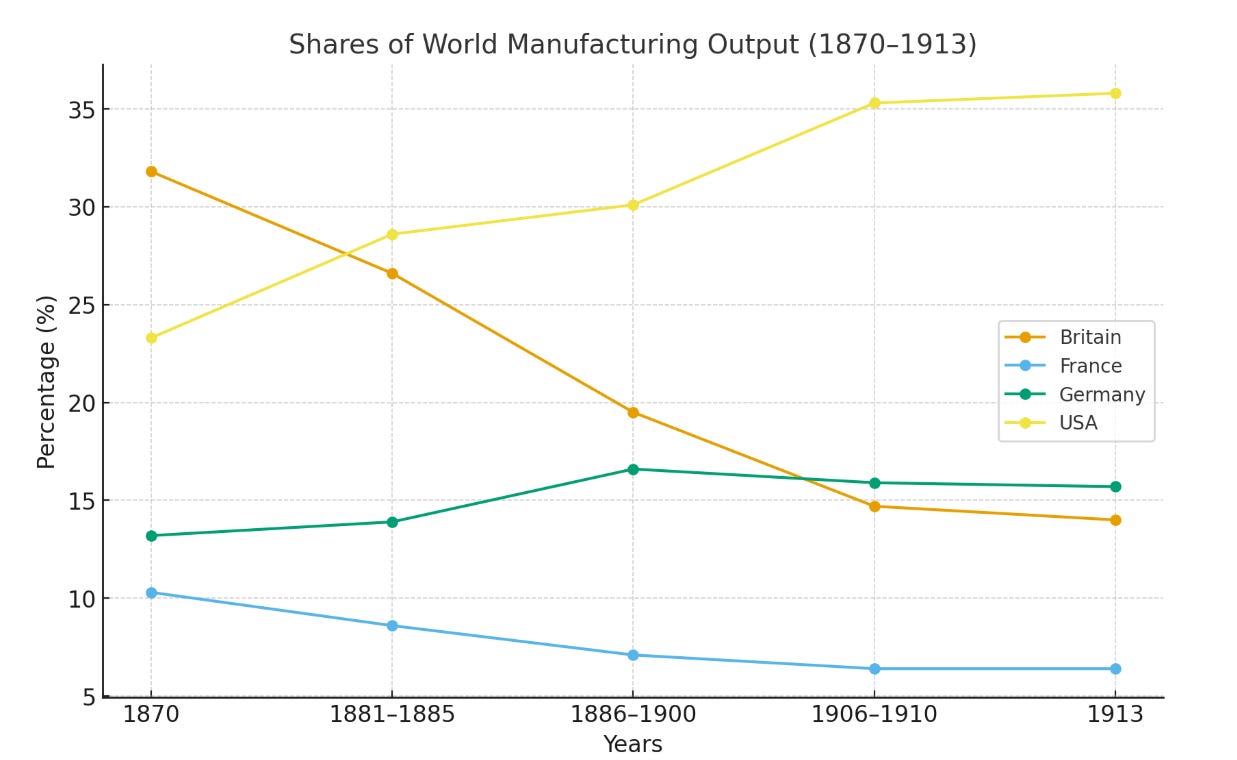

For simpler context, here is a visualization from ChatGPT:

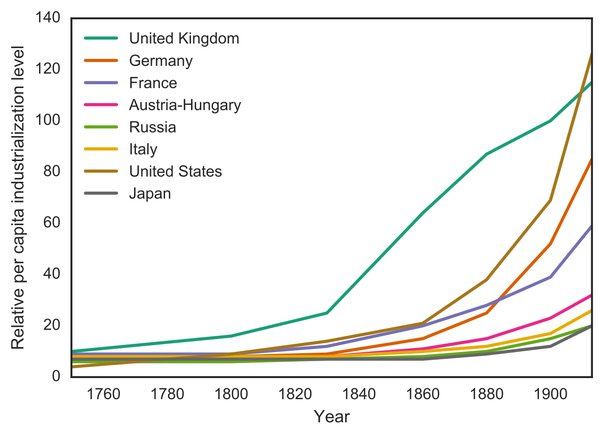

And prior to this, the development of industrial capacity earlier in the 19th century:

source: Paul Bairoch, “International Industrialization Levels from 1750 to 1980,” Journal of European Economic History (1982) v. 11.

Working backwards, it becomes obvious what took place in the 19th and 20th century as a matter of relief against industrial policy: Britain developed massive industrial capacity first, which allowed it to sustain and continually impose greater order on its global empire, which then permitted it to extract materials that allowed them to accelerate the production and distribution of finished goods. Subsequently, the United States, Germany and France followed with equal gusto, with the United States and Germany expanding their assets, trade relationships, and the internal specialization of industrial firms within their economies with sufficient gusto to eventually surpass the United Kingdom.

The decline of Britain’s relative industrial capacity led to a Great Power conflict in World War I, and subsequent weakening of the British Pound as reserve currency all the way through the establishment of the US Dollar as a global, gold-backed reserve currency with Bretton Woods in 1944.

By the same token, the United States had already “taken the lead” from Britain with respect to global manufacturing in about the 1890s, while the cultural similarities and banking relationships between the two countries meant that the United States would ultimately have to come to Britain’s aid in any extended great power conflict, including World War I and ultimately up to Lend-Lease and the semi-official transition of British imperials assets to the United States in he midst of World War II. Had these fallen into German (and, of course, Japanese) hands, the United States stood to lose much in terms of wealth, capital and influence on the global stage.

For the sake of argument, let’s consider this period (1890-1950) as the first historical “Great Industrial Power Transition”, in order to understand the consequences of whose standard of living was highest and where the center of the global financial system was ultimately located. Before 1890, it was clearly the City of London. After 1950, it was most definitively the City of New York.

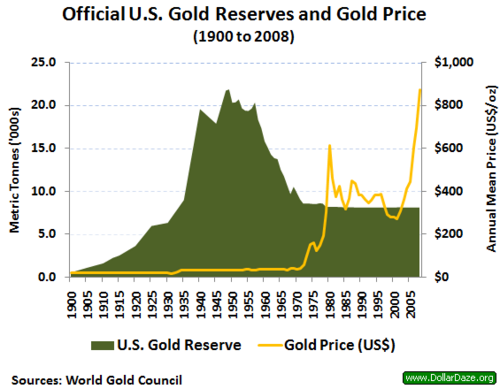

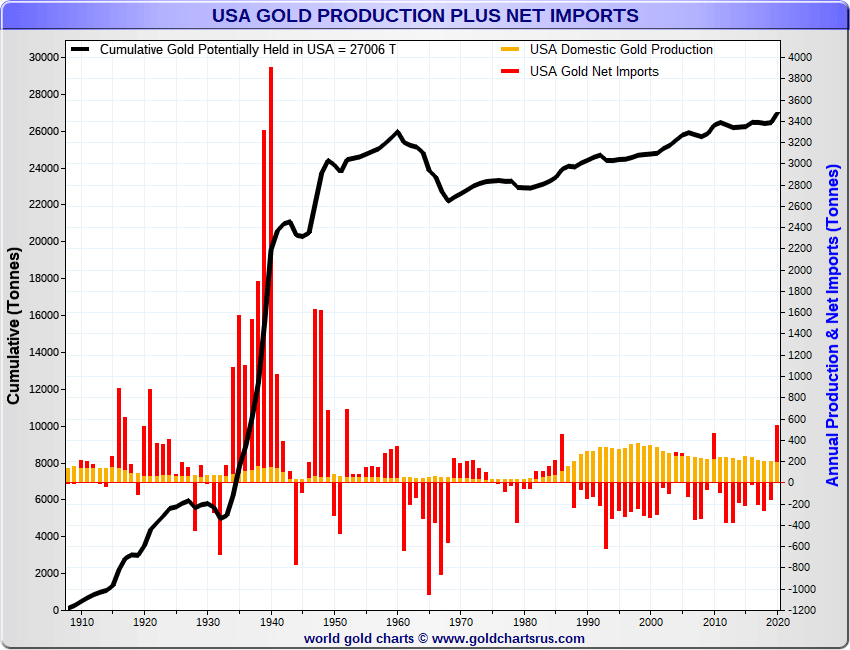

In the beginning of this transitory period, the United States officially surpassed Great Britain in industrial production, and through the entire period of the transition up to 1950, accumulated massive gold reserves as financial ballast representing the unique value of its goods on the global market.

Following the 1950s and as the Marshall Plan and other policy choices sought to prevent the expansion of Soviet Communism on otherwise fertile democratic-capitalist soil, the United States began to print more dollars to support global exporters in developing trade relations with the United States. This began a steady drawdown of US gold reserves through redemptions until the “Nixon Shock” (1971), where the redeemability of US currency in gold was suspended because there were more dollars in circulation than could be redeemed in gold at the $35 USD price per ounce price - agreed to at the 1944 Bretton Woods conference.

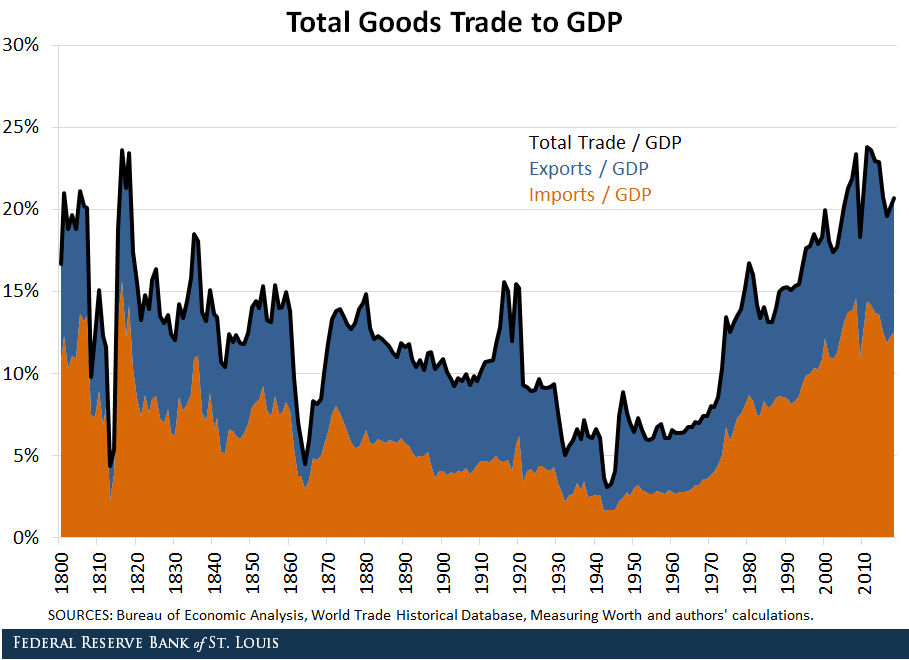

Hence, in the development of the US economy as it relates to both trade and the accumulation of massive riches, it becomes obvious to see that the United States began as an import-dependent economy, slowly building trade surpluses following the Civil War and effectively up to 1945, where the trend gradually begins to reverse again: imports as a percentage of GDP begin to increase substantially in the early 70s (having “funny money” with nothing backing it helps) and subsequently begins to exceed exports in the 1980s up until where we are today, in 2025.

Part of this cycle follows a predictable pattern: nations must trade in order to become rich, but as they become rich, less of their economic activity is represented in trade. Eventually, perhaps, rich nations become lazy, and then that proportion of trade returns in the form of cheap imports to slake consumer appetites without needing to produce much more at all - or simply doing so on debt.

If we apply these principles to a “Second Great Industrial Power Transition” between the US and China, we can understand that the Great Financial Crisis of 07-08 is the singpost for Chinese trade and relative wealth - more than 60% of China’s economic activity is tied up in trade at the high water mark of 2008. In order to recover from the recession, China imposed aggressive spending, real estate and industrial policy which was debt-fueled, but much of the debt was soaked up by internal Chinese savings.

source: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NE.TRD.GNFS.ZS?locations=CN

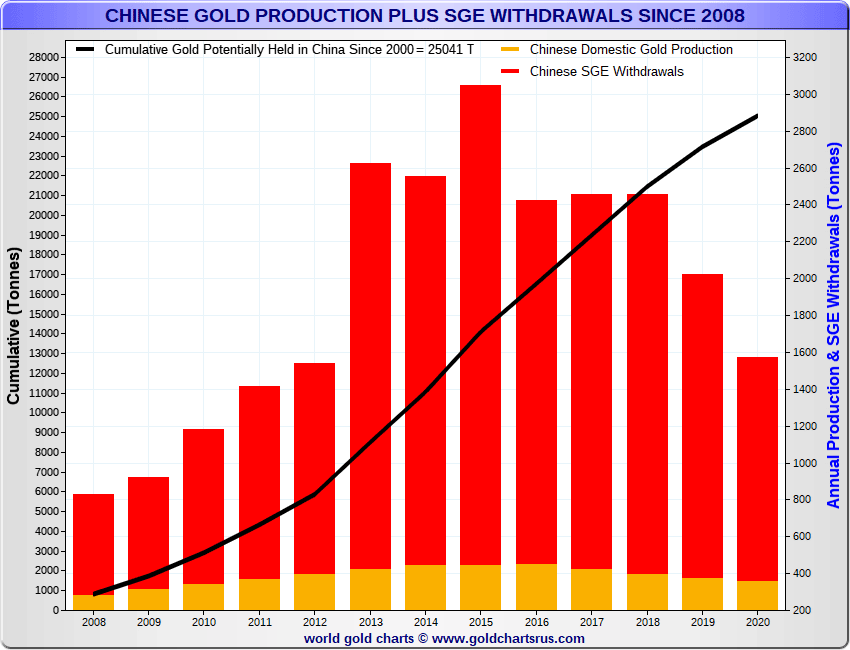

As China’s economy has begun to approach comparability with the United States - firstly on PPP and soon on an absolute basis - China has sought to hedge against the Japanese experience, where forcing relatively strong currency (to adopt a subordinate position on exports) has helped cause decades of domestic economic doldrums. Henceforth from 2008, China began aggressively accumulating gold as a larger component of its FOREX reserves, while Chinese citizens further accumulated even more as a hedge against the debt-inflated Yuan.

source: https://goldbroker.com/news/china-us-gold-accumulation-2283

As of 2021, US and Chinese gold holdings were effectively comparable while the United States saw increasing trade deficits amidst COVID, and the Chinese adopted a much more socially coherent “bunker mentality” which, though punitive, was actually able to provide for the basic needs of a majority of the population. It doesn’t matter what you think of the qualities of a competing social and economic system - if it outproduces you, outworks you, and ultimately aggregates more wealth and prosperity, you don’t have a choice but to do most of what it says when it takes an interest in you. As China maintains a more pre-eminent financial position (with plans already in motion to expand the Shanghai Gold Exchange internationally), the quality of life, financial security of everyday citizens and general level of prosperity will continue to rise, exceeding the equivalent situation for citizens of the West firstly in economic aggregates and perhaps eventually on a “per capita”, everyday basis.

As of today, this is not a question of ideology, but of actual outcomes. Or, as Deng Xiaoping might say, “you judge a cat by whether it catches mice”.

Why Did This All Happen?

Ultimately, there’s no reason to speculate on what exact historical process led to the bifurcation of the West into haves and have-nots. C. Wright Mills’ The Power Elite may be a good start in order to understand what happened in America - regional elites who were previously accountable to the broader US population gradually moved to the coasts and lost interest, and as outsourcing, union-busting, or any number of globalization-based policies took hold, those previously invested populations lost hope and interest all the same.

Whatever the process, reversing it involves a major transition in both the global financial order and the scale of US involvement in industrial policy. The trap here is that the US cannot simply buy gold to the extent that the Chinese can, because as more US dollars chase gold, the price will increase in orders of magnitude. We are effectively observing this, whether we like it or not, while massive inflationary policy is the only way for the United States to get out of its debt conundrum, but with inflation to what end. If it only goes directly into the stock market, bypassing meaningful industrial investment, it will contribute nothing to resolving the long term industrial lag in the US economy. If it goes to subsidizing consumption - e.g. as new “stimmies” in the form of “tariff rebates” - that money will simply go back out the door, with the US government perhaps collecting an increased vig on the way out.

The only solution is for the United States to make stuff that people want. It did that with the iPhone, except it contracted out the actual manufacturing to China. Can anybody name another product that it accomplished this within the past two decades except for digital services which are 1) relatively easy to substitute and 2) attract a lot of attention both for fines (e.g. from Canada and the EU) and as a tool of the US surveillance state?

Apple does collect 80% of global smartphone profit share at last count, but is this really an American approach? Some component of the US economy acts as Switzerland, Germany, Norway or the Netherlands might - basically designing and executing on global-leviathan business plans through outsourcing while maintaining key engineering and technical expertise domestically - however the United States doesn’t have a German-style worker training program, a Norwegian sovereign wealth fund, a Swiss investment in high-tech education, or a Dutch social welfare state. It has a concentration of “top talent”, and the other 80% effectively live in servitude to them, whereas China - though with its own inequalities - creates gainful employment for a larger portion of its population, and builds the necessary machine capacity and sovereign wealth to sustain that system into the future.

No one seems to want a cataclysmic Great Power transition in the matter that was experienced through World War II, but looking at Detroit or other US industrial cities, one might assume that the effects are essentially the same, and there are lessons to learn there. As has been understood since the late 19th century, a nation’s industrial capacity does much to determine its survival in both war and peace. The Soviet Union, upon the introduction of Five Year Plans, sought to collectivize agricultural in order to concentrate import dollars in government hands so that it could invest in new machine capacity. Upon the death of Mao, China’s economic policy gradually changed to be more open to the West, leveraging a massive underutilized labor force to slowly build domestic expertise and technical capacity.

Perhaps, in the southeast Asian context, the sheer mass of population and the historical habits of rice farming simply have simply proven a more effective system for accumulating wealth than the seasonal aspects of wheat farming and tinkering in the doldrums that predated Western global expansion. Maybe it’s the simple fact that, in the context of Asian industrial development, global preeminence is simply an idea whose time has come. Ultimately, societies that maintain a strong sense of purpose, with sufficient scientific and industrial capacity, are the ones best suited to project power globally. China has the lead in this, but as we constantly remind ourselves, it has its own problems.

So what if conflict does arise? Well, it might have a pretty substantial historical precedent: in the closing months of World War II, German forces on their western front could not help but feel demoralized. American infantrymen were equipped like officers, they burned more gasoline than the Germans had on hand just to prevent them from capturing it, American artillery fire was deadly synchronized and efficient, and a single company of American soldiers would have more radios on hand than an entire German battalion.

The America that generated that resounding victory against Nazi Germany did so with unparalleled industrial might, logistical capability and technological advancement which superseded even the most artful players in Old Europe. American innovation was a product of rigorously educated farm laborers who transitioned first to factories and then to the stars. America today is a hollowed out shell of that previous civilization, capable, surely, but with neither the human or physical capital left to muster new energy towards any great national goal - only one tech bubble after another and endless private speculation without ever looking past quarterly returns.

And the irony is not that this particular historical pattern could be repeating itself, but one nested within it: arrogance. When confronted with the idea that the United States would produce 50,000 planes to defeat the Germans in WWII, Herman Goering assured Adolf Hitler: “The Americans cannot build airplanes. They are very good at refrigerators and razorblades.” Surely, at the time, Germany’s industrial goods could make up for quantities of 2 or 3 to 1 on simple quality alone, but ultimately, they could do nothing at 10:1, 50:1, or beyond - and at that gap, the balance of quality seemed to tilt to America as well.

Today in the United States and the Western World, many still treat China with the same arrogance as was the case - or perhaps “justified” - 15 or 20 years ago, but the balance is not the same. The scales have shifted. In this context, it is important to do something, anything, except for what we have been doing up to this point - not simply to “compete” with China, but simply to survive with some matter of dignity and self-respect for the majority of our populations. The answer may take on a flavor of “Capitalism with American characteristics” (again, homage to Deng Xiaoping), but the reality is, with the historical ethics and attitudes that prevail in the West, our modern sense of rigidity, our overly bureaucratized business culture, and our unwillingness to take risks on whacky ideas (who would realistically believe in “bone glue” East of the Taiwan Strait?) are the only answer to compete with Future China on quality of life.

The best answer is simple, everywhere you see a creative person, let them do their thing.